- 0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55, 66, 78, 91, 105, 120, 136, 153, 171, 190, 210, 231, 253, 276, 300, 325, 351, 378, 406, 435, 465, 496, 528, 561, 595, 630, 666...

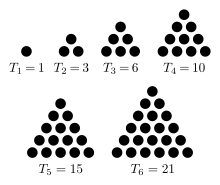

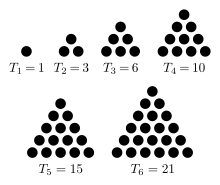

- The first six triangular numbers

The triangle numbers are given by the following explicit formulas:

where

is a

binomial coefficient. It represents the number of distinct pairs that can be selected from

n + 1 objects, and it is read aloud as "

n plus one choose two".

The first equation can be illustrated using a

visual proof.

[1] For every triangular number

, imagine a "half-square" arrangement of objects corresponding to the triangular number, as in the figure below. Copying this arrangement and rotating it to create a rectangular figure doubles the number of objects, producing a rectangle with dimensions

, which is also the number of objects in the rectangle. Clearly, the triangular number itself is always exactly half of the number of objects in such a figure, or:

. The example

follows:

(green plus yellow) implies that (green plus yellow) implies that  (green). (green). |  | |

The first equation can also be established using

mathematical induction.

[2] Since the sum of the first (one) natural number(s) is clearly equal to one, a basis case is established. Assuming the inductive hypothesis for some

and adding

to both sides immediately gives

In other words, since the

proposition

(that is, the first equation, or inductive hypothesis itself) is true when

, and since

being true implies that

is also true, then the first equation is true for all natural numbers. The above argument can be easily modified to start with, and include, zero.

Carl Friedrich Gauss is said to have found this relationship in his early youth, by multiplying

n/2 pairs of numbers in the sum by the values of each pair

n + 1.

[3] However, regardless of the truth of this story, Gauss was not the first to discover this formula, and some find it likely that its origin goes back to the

Pythagoreans 5th century BC.

[4] The two formulae were described by the Irish monk

Dicuilin about 816 in his

Computus.

[5]

The triangular number

Tn solves the

handshake problem of counting the number of handshakes if each person in a room with

n + 1 people shakes hands once with each person. In other words, the solution to the handshake problem of

n people is

Tn−1.

[6] The function

T is the additive analog of the

factorial function, which is the

products of integers from 1 to

n.

The number of line segments between closest pairs of dots in the triangle can be represented in terms of the number of dots or with a

recurrence relation:

In the limit, the ratio between the two numbers, dots and line segments is

Relations to other figurate numbers[edit]

Most simply, the sum of two consecutive triangular numbers is a

square number, with the sum being the square of the difference between the two (and thus the difference of the two being the square root of the sum). Algebraically,

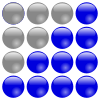

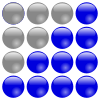

This fact can be demonstrated graphically by positioning the triangles in opposite directions to create a square:

| 6 + 10 = 16 |  | |

| 10 + 15 = 25 |  |

There are infinitely many triangular numbers that are also square numbers; e.g., 1, 36, 1225. Some of them can be generated by a simple recursive formula:

with

with

with

with  and

and

A square whose side length is a triangular number can be partitioned into squares and half-squares whose areas add to cubes. This shows that the square of the

nth triangular number is equal to the sum of the first

n cube numbers.

More generally, the difference between the

nth

m-gonal number and the

nth

(m + 1)-gonal number is the

(n − 1)th triangular number. For example, the sixth

heptagonal number (81) minus the sixth

hexagonal number (66) equals the fifth triangular number, 15. Every other triangular number is a hexagonal number. Knowing the triangular numbers, one can reckon any

centered polygonal number; the

nth centered

k-gonal number is obtained by the formula

where T is a triangular number.

Other properties[edit]

Every even

perfect number is triangular (as well as hexagonal), given by the formula

where

Mp is a

Mersenne prime. No odd perfect numbers are known, hence all known perfect numbers are triangular.

For example, the third triangular number is (3 × 2 =) 6, the seventh is (7 × 4 =) 28, the 31st is (31 × 16 =) 496, and the 127th is (127 × 64 =) 8128.

In

base 10, the

digital root of a nonzero triangular number is always 1, 3, 6, or 9. Hence every triangular number is either divisible by three or has a remainder of 1 when divided by 9:

- 0 = 9 × 0

- 1 = 9 × 0 + 1

- 3 = 9 × 0 + 3

- 6 = 9 × 0 + 6

- 10 = 9 × 1 + 1

- 15 = 9 × 1 + 6

- 21 = 9 × 2 + 3

- 28 = 9 × 3 + 1

- 36 = 9 × 4

- 45 = 9 × 5

- 55 = 9 × 6 + 1

- 66 = 9 × 7 + 3

- 78 = 9 × 8 + 6

- 91 = 9 × 10 + 1

- …

- There is a more specific property to the triangular numbers that aren't divisible by 3, that is, they either have a remainder 1 or 10 when divided by 27. Those that are equal to 10 mod 27, are also equal to 10 mod 81.

The digital root pattern for triangular numbers, repeating every nine terms, as shown above, is "1, 3, 6, 1, 6, 3, 1, 9, 9".

The converse of the statement above is, however, not always true. For example, the digital root of 12, which is not a triangular number, is 3 and divisible by three.

If x is a triangular number, then ax + b is also a triangular number, given a is an odd square and b = a − 1/8

b will always be a triangular number, because 8Tn + 1 = (2n + 1)2, which yields all the odd squares are revealed by multiplying a triangular number by 8 and adding 1, and the process for b given a is an odd square is the inverse of this operation.

The first several pairs of this form (not counting 1x + 0) are: 9x + 1, 25x + 3, 49x + 6, 81x + 10, 121x + 15, 169x + 21, … etc. Given x is equal to Tn, these formulas yield T3n + 1, T5n + 2, T7n + 3, T9n + 4, and so on.

The sum of the

reciprocals of all the nonzero triangular numbers is

Two other interesting formulas regarding triangular numbers are

and

both of which can easily be established either by looking at dot patterns (see above) or with some simple algebra.

In 1796, German mathematician and scientist

Carl Friedrich Gauss discovered that every positive integer is representable as a sum of three triangular numbers (possibly including

T0 = 0), writing in his diary his famous words, "

ΕΥΡΗΚΑ! num = Δ + Δ + Δ". Note that this theorem does not imply that the triangular numbers are different (as in the case of 20 = 10 + 10 + 0), nor that a solution with exactly three nonzero triangular numbers must exist. This is a special case of the

Fermat polygonal number theorem.

Applications[edit]

A

fully connected network of

n computing devices requires the presence of

Tn − 1 cables or other connections; this is equivalent to the handshake problem mentioned above.

In a tournament format that uses a round-robin

group stage, the number of matches that need to be played between

n teams is equal to the triangular number

Tn − 1. For example, a group stage with 4 teams requires 6 matches, and a group stage with 8 teams requires 28 matches. This is also equivalent to the handshake problem and fully connected network problems.

One way of calculating the

depreciation of an asset is the

sum-of-years' digits method, which involves finding

Tn, where

n is the length in years of the asset's useful life. Each year, the item loses

(b − s) × n − y/Tn, where

b is the item's beginning value (in units of currency),

s is its final salvage value,

n is the total number of years the item is usable, and

y the current year in the depreciation schedule. Under this method, an item with a usable life of

n = 4 years would lose

4/10 of its "losable" value in the first year,

3/10 in the second,

2/10 in the third, and

1/10 in the fourth, accumulating a total depreciation of

10/10 (the whole) of the losable value.

Triangular roots and tests for triangular numbers[edit]

By analogy with the

square root of

x, one can define the (positive) triangular root of

x as the number

n such that

Tn = x:

[11]

which follows immediately from the

quadratic formula. So an integer

x is triangular if and only if

8x + 1 is a square. Equivalently, if the positive triangular root

n of

x is an integer, then

x is the

nth triangular number.

[11]

Wikipedia