1. Infinite Sets

Whereas sets like {1,2,3} and {dog, cat, apple, bat} clearly are finite in size (with size 3 and 4 respectively), it is natural to say that the set of all integers and the set of real numbers have infinite size. What is particularly interesting though is that while both infinite sets, the integers have an infinite size that’s smaller (in a precise sense) than that of the real numbers.

To observe this, we begin by noting that we can relabel the elements of {dog, cat, apple, bat} to be {1,2,3,4} by assigning dog=1, cat=2, apple=3, bat=4, which does not alter the size of our set (since the size of a set is independent of the names given to its items). However, {1,2,3} is obviously a subset of {1,2,3,4}, so {1,2,3} cannot be larger in size than {1,2,3,4}, and therefore {1,2,3} cannot be larger than {dog, cat, apple, bat} since this set was constructed from {1,2,3,4} just by renaming elements. More generally, if one (finite) set is larger than another, then we can always relabel the larger set so that the smaller one becomes a subset of it. Let’s now assume that this property continues to hold for infinite sets (or, if you like, we can use this very natural property as part of the foundation for the definition of the sizes of infinite sets).

Now, we apply this

reasoning about relabeling to the real numbers and integers. First, we observe

that the integers are a subset of the real numbers, and hence cannot have size

larger than the real numbers. On the other hand though (and this is subtle

requiring proof, which can be found here and here) it is impossible to relabel the

integers in such a way that the real numbers become a subset of them. Hence, the

real numbers are indeed larger than the integers in some important sense.

It may seem obvious that the size of the set of real numbers is in some sense a larger infinity than that of the size of the integers. What may come as a greater surprise however, is that the set of integers {…, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, …}, the set of positive integers {1, 2, 3, 4, …}, and the set of all rational numbers {p/q where p and q are integers and q > 0} are all infinite but have exactly the same infinite size. The reason is simply because relabelings of these sets exist that make them all into the same set. For example, note that the assignment 1=0, 2=1, 3=-1, 4=2, 5=-2, 6=3, 7=-3, etc. will turn the positive integers into the set of all integers.

As it turns out, there is an infinite “chain” of infinities that measure the size of sets, including

(a) Accept the fact that this mathematical question in unanswerable or “outside of math”.

(b) Reject the existence

of sets that are larger than the integers and smaller than the real numbers

which would be confirming what is known as the Continuum Hypothesis and amounts to adding a

new axiom to math.

(c) Accept the existence of sets with this in between size, which implies adding the existence of such sets as a new mathematical axiom.

2. Limits

Infinities often arise when using “limits”, mathematical constructions which provide a rigorous backbone for calculus. When we have a function

what we mean is the value (if one exists) that the function

since by making

since as x gets larger and larger,

and

whereas

so

3. Algebra

Yet another way to think about infinity, is to introduce it as a special “number” with certain properties. For example, we can define

Similar rules could be used to define

Defining each of these latter statements is problematic. However, as long as we never need to multiply infinity by zero, or divide infinities, or do any other “undefinable” operations in whatever context we happen to be working, we can introduce

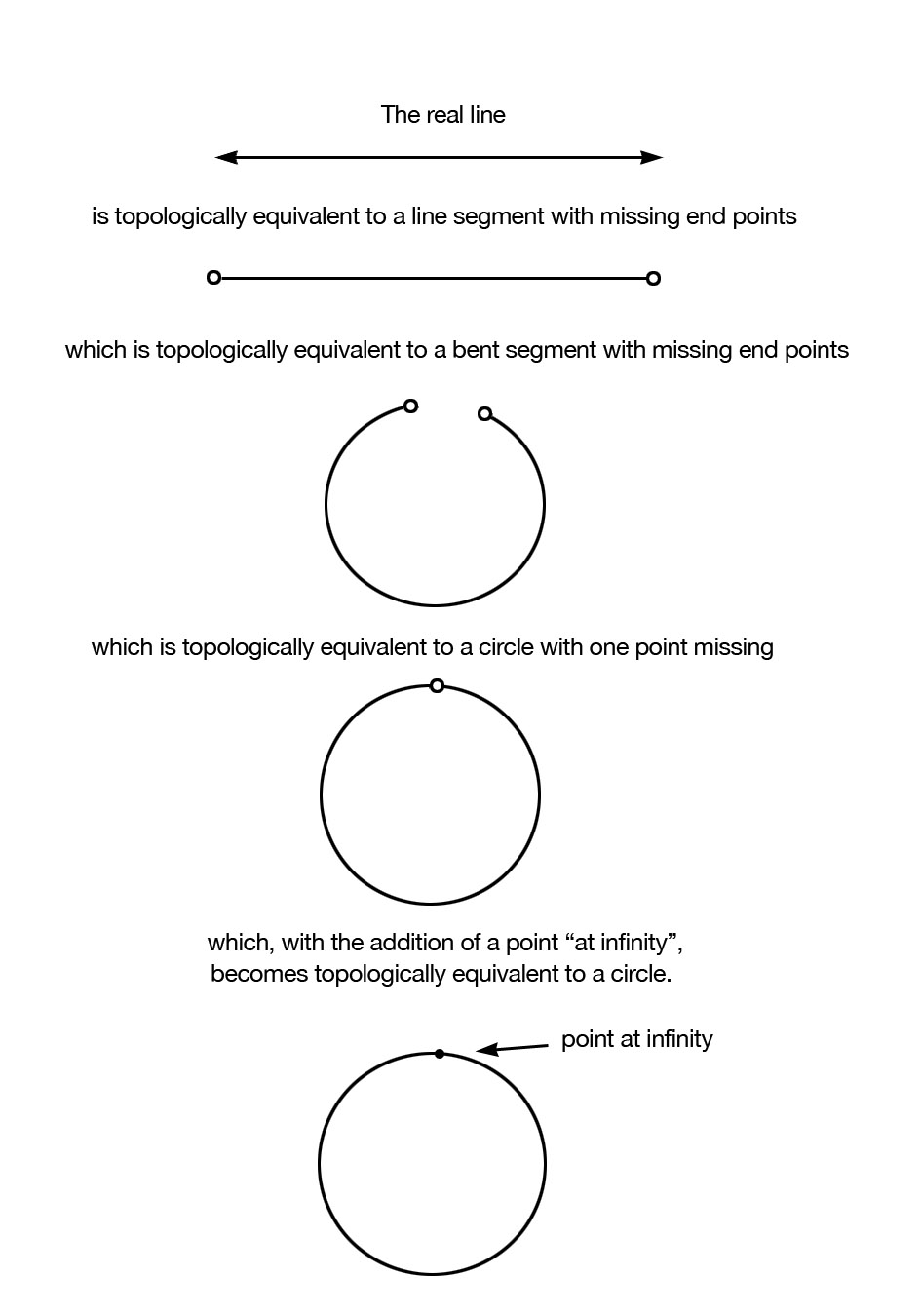

4. Topology

Topology is the study of topological spaces (which are sort of like a generalized notion of surfaces) and the properties they have that are independent of angles and distances. If two surfaces can be made the same through stretching or pulling without requiring any cutting or gluing (more technically, if they can be mapped onto each other by a continuous function with a continuous inverse) then they are considered identical from a topological perspective. Hence, a disc and rectangular surface are topologically equivalent, as are a rubber band shaped surface and a disc with one hole punched in it (imagine stretching the hole until you get a band like object). You may begin to see why it has been said that a topologist is a person who can’t tell a teacup from a doughnut.

When topologists work

with the real number line (i.e. the set of real numbers together with the usual

notion of distance which induces topological structure), they sometimes

introduce a “point at infinity”. This point, denoted  can be thought of as the point that you would always be heading towards if you

started at 0 and traveled in either direction at any speed for as long as you

liked. Strangely, when this infinite point is added to the real number line, it

makes it topologically equivalent to a circle (think about the two ends of the

number line both joining up to this single infinite point, which closes a loop

of sorts). This same procedure can also be carried out for the plane (which is

the two dimensional surface consisting of points (x,y) where x and y are any

real numbers). By adding a point at infinity we compactify the plane, turning it into

something topologically equivalent to a sphere (imagine, if you can, the edges

of the infinite plane being folded up until they all join together at a single

infinity point).

can be thought of as the point that you would always be heading towards if you

started at 0 and traveled in either direction at any speed for as long as you

liked. Strangely, when this infinite point is added to the real number line, it

makes it topologically equivalent to a circle (think about the two ends of the

number line both joining up to this single infinite point, which closes a loop

of sorts). This same procedure can also be carried out for the plane (which is

the two dimensional surface consisting of points (x,y) where x and y are any

real numbers). By adding a point at infinity we compactify the plane, turning it into

something topologically equivalent to a sphere (imagine, if you can, the edges

of the infinite plane being folded up until they all join together at a single

infinity point).

In some sense these “points at infinity” that are introduced are not special in any way (they behave just like all other points from a topological perspective). However, if measures of distance are thrown back into the mix, it seems fair to say that these points at infinity are infinitely far away from all the others.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the question “what is infinity?” is not one that really can be answered, as it assumes that infinite things have a unique identity. It makes more sense to ask “how do infinite things arise in mathematics”, and the answer is that they arise in many, very important ways.

Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

댓글 없음:

댓글 쓰기